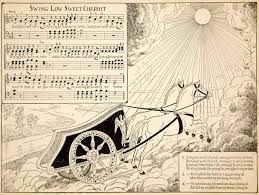

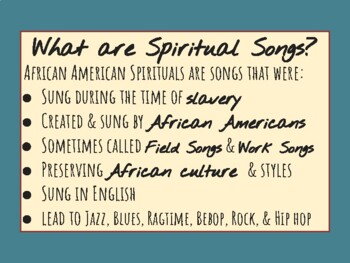

Most of the songbooks available to us today are dotted with beautiful, traditional songs identified not by any named composer or lyricist but simply as “African-American Spiritual.” Most of these we have listened to, sung, and played nearly all of our lives. Needless to say, there is a good backstory to all this—one we should know.

While these songs originated in and were common throughout the American South during slavery days, they were virtually unknown in the American North until the late 19th century.

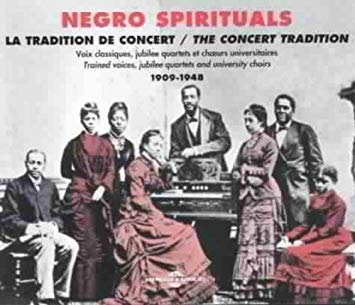

Credit for telling this “spiritual story” goes to a group of students and faculty of Fisk College, a historically African-American school in Nashville, Tennessee, who “took their music on the road” with the hope of raising funds for their cash-strapped school.

This was back in 1871 and their early repertoire consisted mostly of traditional spirituals—songs handed down orally, not from published hymn books, and sung a cappella. Their original tour took them along the route of the historic Underground Railroad and eventually they toured in England and Europe.

Fisk College was founded after the end of the Civil War to educate freedmen and other young African-Americans. After its first five years, however, the university was facing serious financial difficulty. To avert bankruptcy and closure, Fisk’s treasurer and music director, George L. White, . . .

. . . a white Northern missionary dedicated to music and proving African-Americans were the intellectual equals of whites, gathered a nine-member student chorus, both men and women, to go on a singing tour to earn money for the university. The group of students, consisting of two quartets and a pianist, started their tour under White’s direction.

Taking sabbaticals on and off from their studies over the next eighteen months, the group toured through Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. After their first concert in Cincinnati, the group donated their small profit, which amounted to less than sixty dollars, to the relief to the victims of the great Chicago fire that had just occurred. Another form of gift!

Click or tap on the triangle in the next image to hear them sing a song new to their audiences.

The group traveled on to Columbus, Ohio, where lack of funding, poor hotel conditions, and overall mistreatment from the press and audiences left them feeling tired and discouraged. The group and their leader gathered and prayed about whether to continue with the tour. They decided to go on but White believed that they needed a name to capture audience attention. The next morning, he met with the singers and said “Children, it shall be Jubilee Singers in memory of the Jewish year of Jubilee.” This was a reference to the biblical “Year of Jubilee” in which all slaves would be set free. Since many if not most of the students at Fisk University and their families were newly freed slaves, the name “Jubilee Singers” seemed

fitting.

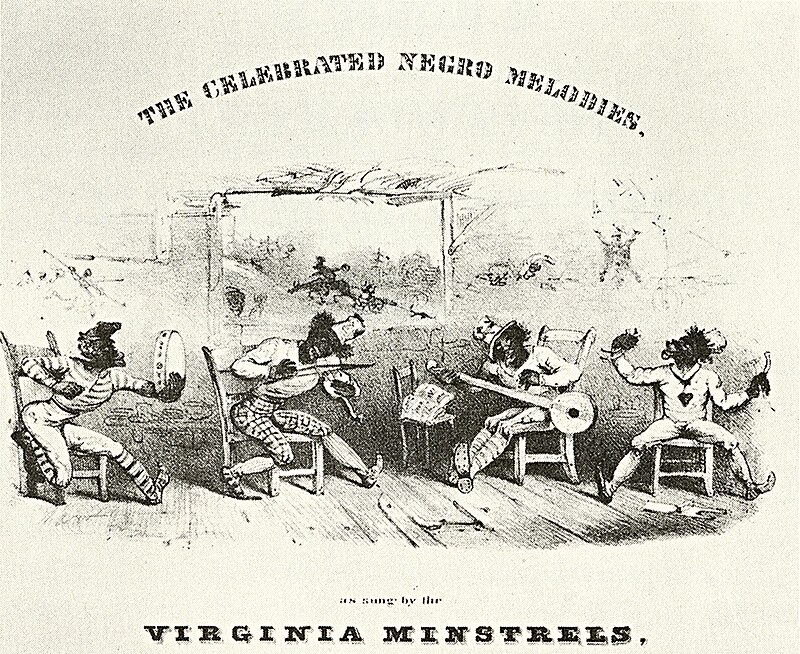

The Jubilee Singers’ performances were a departure from the familiar “black minstrel” genre of white musicians’ performing in blackface and, not surprisingly, more or less of a puzzle to the critics and audiences of the time.

One early review of the group’s performance was headlined “Negro Minstrelsy in Church–Novel Religious Exercise,” while further reviews highlighted the fact that this group of “Negro minstrels were, oddly enough, genuine negroes,” not the burnt cork caricatures of negro minstrelsy so familiar to most audiences of the day.

This was not a uniquely American response to the group’s performance, but was typical of European audiences as well.

As the tour continued, however, audiences came to appreciate the singers’ voices, and the group began to be praised. So, historically, the Fisk Jubilee Singers are credited with the early popularization of the Negro Spiritual tradition in the 19th century—particularly among white and northern audiences, many of whom were previously unaware of this musical genre.

Audiences soon began to appreciate the wonderful beauty and power of the songs and, after the rough start, the first United States tours eventually earned $40,000 for Fisk University.

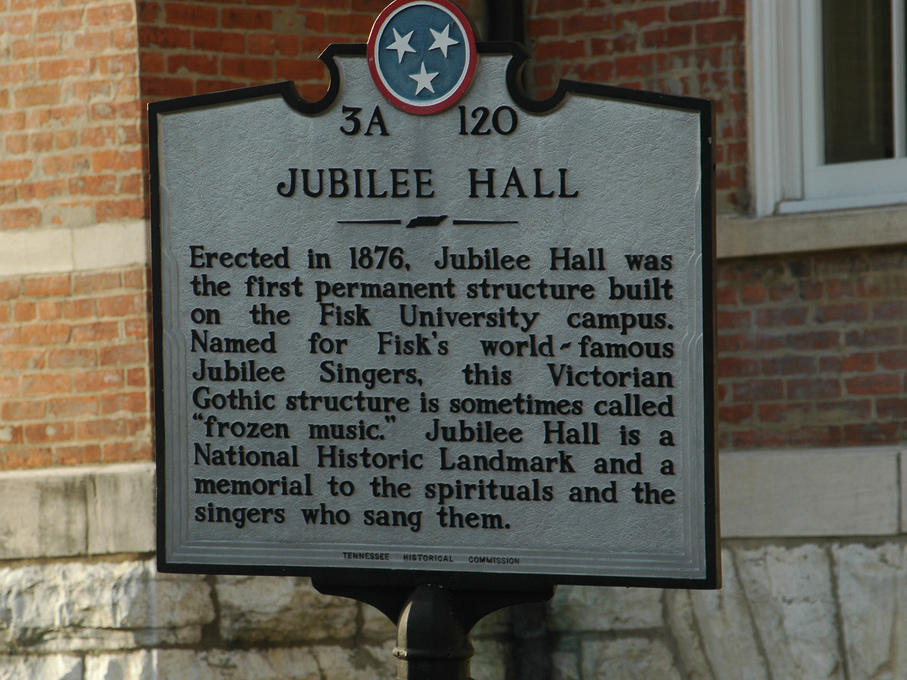

The singers then toured Great Britain and Europe, New York and Washington, and by 1878, had raised over $150,000 for the university. These funds were used to construct Fisk’s first permanent building named, appropriately, Jubilee Hall. The building still stands and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1975—a building made with, if not of, music.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are still touring and performing around the world today and, in 2008, they were awarded a National Medal of Arts—not bad for what began a century and a quarter ago as a simple fundraiser!

Click or tap on the triangle in the next image to hear the singers do something a bit more contemporary!

Their biggest legacy, however, is the sparking of an appreciation throughout the United States and the World for a true American musical art form—the African-American Spiritual.

Click or tap on the triangle in the next image for more, much more!

So, as we sing any of these songs from our songbooks, know that they came from the dark days of slavery to the bright lights of today. A gift to us all.

Stay Tuned!